Creative Creatures

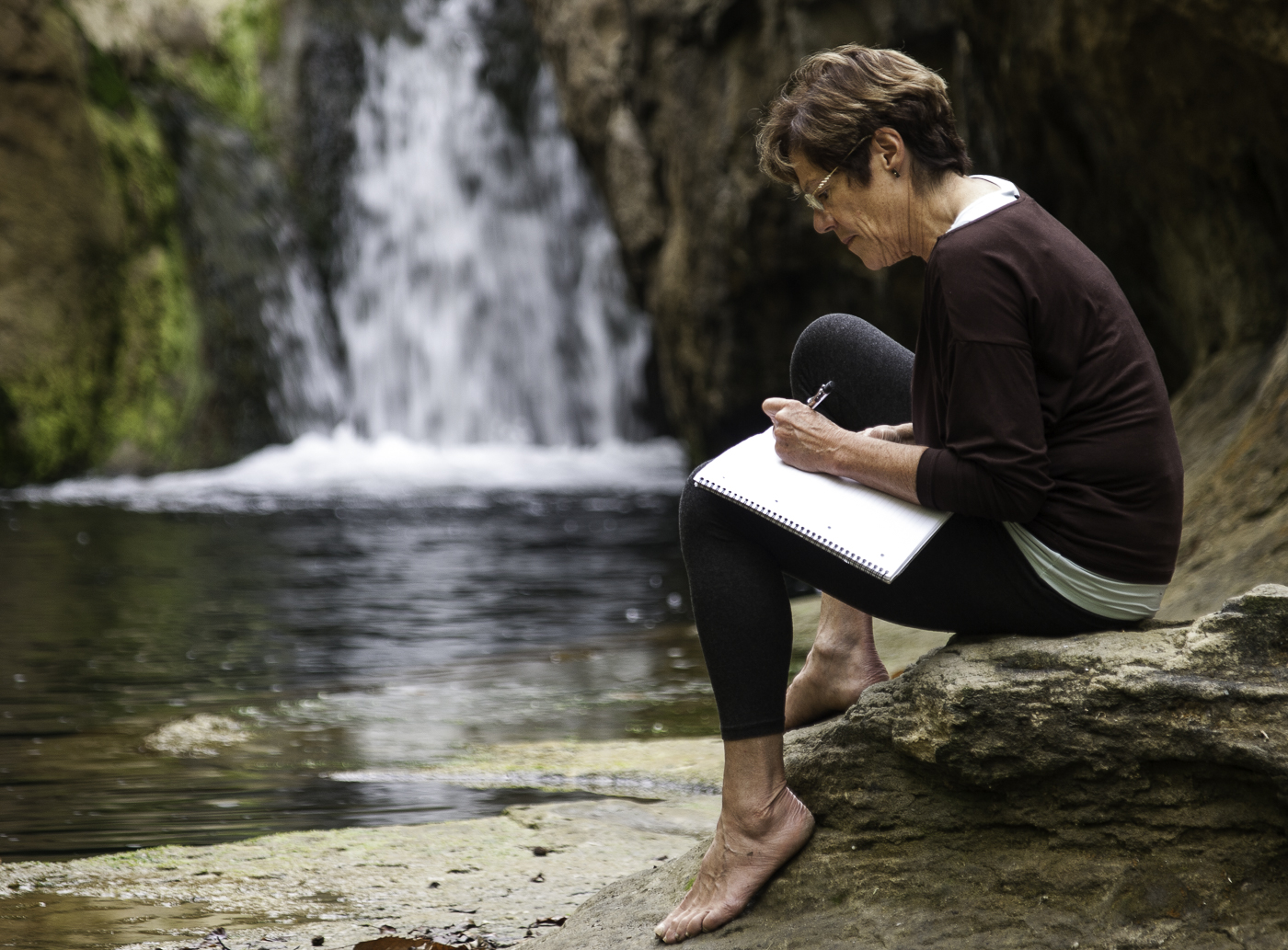

/The first step on the journey to finding our storyteller-hero, our writer in-the-wild, is to realise that throughout our lives, like a great artist, we are continually making creative choices.

Our lives are like clay, malleable and full of potential.

The force of the imagination in the human being is not to be underestimated. As Jonathan Gottschall remarks in his book ‘The Storytelling Animal’, human beings have no trouble at all making things up, i.e. telling stories. In fact, we have trouble not making a narrative out of anything and everything we come across!

Creativity infects everything.

Let’s look at the example of deciding to write an autobiography. Ever noticed that in the re-telling of a past event, those who were present can have completely different memories of what happened? In the very act of making memories we select and edit the material of our lives. And when we write down our life story, we necessarily re-edit our already creative memories, to make the narrative work.

It’s not only in re-viewing and recording the years of our life gone by, that we make creative choices. We do it in every new life situation we encounter. We always have a choice as to how we think and act (even if the range of choices available is not necessarily what we would wish). We can realise this, take responsibility for our choices, and thereby feel in control of our life, or, we can see ourselves as a victim of life events over which we have no control. The former gives us strength and health. The latter brings fear and ill health.

Our ability to make choices in our life as a whole feeds in to how well we make choices during the storytelling and writing process. It also gives rise to the evidence observable on the page, and the clues held in the tone, vocabulary, grammar and rhythm of our spoken words. When we make pro-active choices at appropriate times in the storytelling process, we come closer to behaving like the truly wild animal, responding appropriately to its environment. We become better speakers and writers. Writers-in-the-wild.

Our words are like clay, equally malleable and full of potential.

It’s time to stop thinking of them as flat and unmoving on the page, or as lacking grace, flow and passion when they leave our mouths. It’s time to start regarding them as wild animals in the woods, clay in our hands. They are a physical substance that can be bent shaped moulded, and toyed with until a powerful form arises, seemingly of its own volition.

We unpeel those layers that have attached themselves over time, by finding word portals back to a freshness of thought and expression.