Being A Better Boss

/When I write, I divide my inner world in two. There’s the writer, and there’s the editor. Often they have an employee-boss working relationship.

Read MoreBlog

The ‘Aha!’ moment of the reader is also the instant the writer is liberated. To get there, write as if experiencing something for the first time.

Use humour on the page – especially in situations that aren’t at all funny…

Move into close detail – of both inner and outer experience…

Once, in millennium not long before this one, I lived in a Forest…

Martha’s story began, in the way of many, as a glimmer in the back of my mind…

Winter Solstice Competition Runner-up: Hannah Ray, with You Were Born in a Pandemic

When I write, I divide my inner world in two. There’s the writer, and there’s the editor. Often they have an employee-boss working relationship.

Read MoreGreat storytelling coming as much from an embodied place, a place of emotion, body sensations and sensory impressions, as from our heads.

Read More‘Finding your voice’ is bandied about as the gold at the end of the rainbow for emerging writers and storytellers.

Read More

So, why is it that we are ‘natural storytellers’? Recent scientific evidence backs up what we, as writers, know in our guts. Telling stories is not a luxury for human beings, it is vital to our survival and flourishing. If the wild animal has senses, bodily sensation, emotion, action and most probably some powers of imagining and ‘thinking’, to keep it alive, we have all this plus a more developed rational mind, and the ability to tell stories.

There are stories everywhere around us, in films, on TV, and in books. Adverts tell us stories to persuade us to buy their products. Televised sports are also stories. Our heroes face the opponents, with a clear aim, and battle it out to the bitter end. Stories rescue human beings when life is too harsh, too fast, too heavy. We default into daydreaming whenever we are not involved in an immediate, absorbing task. Stories provide rest and relief. They calm our body and mind.

I see the extreme of storytelling as a life-saving strategy in my work as a psychotherapist. Many people who experience traumatic or abusive situations, use storytelling to survive emotionally, when contact with ‘reality’ would be overwhelming for body and mind. Indeed, the state of ‘dissociation’, of feeling detached from a situation that would otherwise be unbearable, often involves elements of storytelling. Below is the account of an abuse survivor.

I could see the window from where I lay. When it was happening, I would look out of the window at the birds flying. I would imagine I too was flying, and that I could go anywhere, do anything. I would visit beautiful places and talk to kind people who reassured me that I would survive. I believe this is what stopped me from going crazy, or from killing myself.

In recent studies of dreams it has been found that 80 percent are about ‘a problem that needs to be solved’. So, it may be that the primary evolutionary role of stories is as, psychologist and novelist Keith Oatley puts it, to be...

…the flight simulators of human social life.

Writing, telling, reading, or listening to stories, activates the same biological process as living out the actions would do. The same neurons fire, and neural pathways are strengthened when we think about performing an action, as when we perform it for real. That’s the reason that professional sports people use visualisation as a key part of their training. Stories allow us to encounter various life obstacles in symbolic guise and to practice ways of solving them, without endangering ourselves. Stories train us for life.

Certainly, stories also play other crucial roles in our lives: They allow us to process emotions. They allow us to feel in control of, and gain perspective on our lives. They can lead to public recognition and (sometimes) money. Autobiographical work can pass information on to future generations, and provide closure to our lives. Stories entertain. They inspire and they motivate.

As I wrote as part of the content for a University of Exeter creative writing course,

When we tell our stories details unfold like flowers, clues become moments of epiphany, feelings are processed, and stuck energy is discharged. We begin to notice the patterns that repeat through our lives, called ‘Repetition Compulsion’ by Sigmund Freud. We see which of those serve us, and which don’t. We can bring closure to the unfinished aspects of our lives. We can grieve and move on. We can find or create our self in the writing.

Storytelling, on the very physical level of our nervous systems, discharges energy. This energy, if it remains trapped, can disable our effective functioning in the world, as well as lead to ill health.

Above all, writing is a fabulous thing to do, because, as poet John Keats so clearly elucidated, the great beauty of the art and craft of it is that ‘it makes everything interesting’.

What I’d like you to take away this month, is the following:

Your job- that of being a wordsmith- is sacred, because without it, the human species cannot survive.

What we need to do as storytellers is to rest in the knowledge that not everything has to come from the rational mind. If we can trust our innate ability to tell stories, to allow our organic movement towards health, then we have truly set out on the trail to re-finding our wild words. So, as the unanswered emails pile up, and as your partner, parents, and children tug relentlessly on your sleeve, remember this: you’re doing war-work. Writing saves lives.

Now how are your mind and body feeling? Would you know how to put the strength of your embodied experience into words?

Onward and upward!

To see the Writing Prompt that accompanies this article, you'll need to sign up on the Wild Words website homepage to receive the Monthly Newsletter, or join the Wild Words Facebook group

Our lives are like clay, malleable and full of potential.

The force of the imagination in the human being is not to be underestimated. As Jonathan Gottschall remarks in his book ‘The Storytelling Animal’, human beings have no trouble at all making things up, i.e. telling stories. In fact, we have trouble not making a narrative out of anything and everything we come across!

Let’s look at the example of deciding to write an autobiography. Ever noticed that in the re-telling of a past event, those who were present can have completely different memories of what happened? In the very act of making memories we select and edit the material of our lives. And when we write down our life story, we necessarily re-edit our already creative memories, to make the narrative work.

It’s not only in re-viewing and recording the years of our life gone by, that we make creative choices. We do it in every new life situation we encounter. We always have a choice as to how we think and act (even if the range of choices available is not necessarily what we would wish). We can realise this, take responsibility for our choices, and thereby feel in control of our life, or, we can see ourselves as a victim of life events over which we have no control. The former gives us strength and health. The latter brings fear and ill health.

Our ability to make choices in our life as a whole feeds in to how well we make choices during the storytelling and writing process. It also gives rise to the evidence observable on the page, and the clues held in the tone, vocabulary, grammar and rhythm of our spoken words. When we make pro-active choices at appropriate times in the storytelling process, we come closer to behaving like the truly wild animal, responding appropriately to its environment. We become better speakers and writers. Writers-in-the-wild.

It’s time to stop thinking of them as flat and unmoving on the page, or as lacking grace, flow and passion when they leave our mouths. It’s time to start regarding them as wild animals in the woods, clay in our hands. They are a physical substance that can be bent shaped moulded, and toyed with until a powerful form arises, seemingly of its own volition.

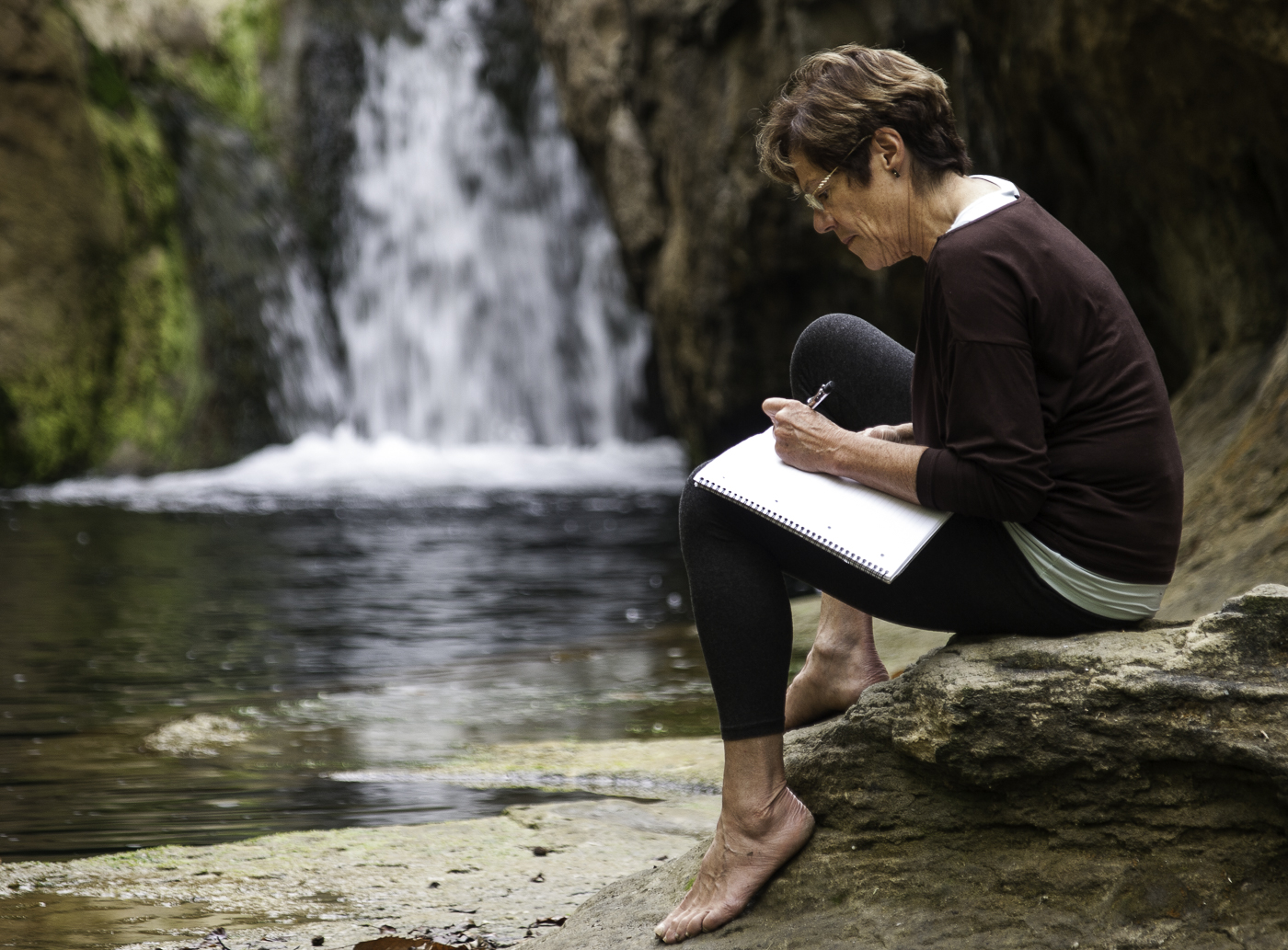

The Wild Words Retreat. Photographed by Peter Reid.

Reading or listening to stories imbued with emotion stimulates much more of the brain than reading an emotionless account would do. The empathy areas light up, and oxytocin, a chemical related to feelings of love and trust, is released.

When our words are imbued with emotion, for both the storyteller, and the listener or reader, it’s like having the wild animal very close, breathing down our neck.

These wild words hook the reader. The power and the passion within them sweeps us along, all the way to the end of the story. There is nothing tame about these words, nothing predictable. They live in extremis. One moment the receiver is roused to laughter and joy, the next they are devastated by tragedy. Hooked by emotion, they journey with the narrator/lead character. It’s quite a trip.

Rachel Shirley gives a relevant example of how to work with emotion on the page. She explains that you could write,

She waited by the door. She felt so frightened, she thought she would begin to panic.

However, it would be stronger to write,

She waited by the door. Her heartbeat thrummed against her ribcage, her mouth tasted like iron and her breaths hitched in her throat.

Although wild words are infused with emotion, as you’ll have noticed in the above example, the emotion is often not named on the page.

Instead the experience of feeling emotion in the body, which is actually the experience of the intensifying of bodily sensations, is described. As these experiences are common to all of us, we know exactly what emotion is being experienced, even if it’s not named. Indeed, it’s more impactful for not being named.

Below is a wonderful (if stomach turning) example of how to work with emotion on the page, from Ian Fleming’s ‘Casino Royal’. Le Chiffre is torturing Bond. Notice how the emotions are never named, but there is attention to the detail of bodily sensations.

Bond's whole body arched in an involuntary spasm. His face contracted in a soundless scream and his lips drew right away from his teeth. At the same time his head flew back with a jerk showing the taut sinews of his neck. For an instant, muscles stood out in knots all over his body and his toes and fingers clenched until they were quite white. Then his body sagged and perspiration started to bead all over his body. He uttered a deep groan.

Wild Words - Nature-inspired creative writing for wild writers and storytellers with Bridget Holding.

Wild Words is a call to express the wild in you. For anyone who has a yearning to express themselves. In conversation, spoken word, storytelling, songwriting, writing (poetry and prose, fiction and non-fiction).

Website by a monk

We unpeel those layers that have attached themselves over time, by finding word portals back to a freshness of thought and expression.