The Body Knows

/Playing with words and images in the mountains of the Pyrenees. Peter Reid carries the camera. I carry the notebook. This is the first in series of images that records our cavorting, and creative collaboration.

Blog

The ‘Aha!’ moment of the reader is also the instant the writer is liberated. To get there, write as if experiencing something for the first time.

Use humour on the page – especially in situations that aren’t at all funny…

Move into close detail – of both inner and outer experience…

Once, in millennium not long before this one, I lived in a Forest…

Martha’s story began, in the way of many, as a glimmer in the back of my mind…

Winter Solstice Competition Runner-up: Hannah Ray, with You Were Born in a Pandemic

Playing with words and images in the mountains of the Pyrenees. Peter Reid carries the camera. I carry the notebook. This is the first in series of images that records our cavorting, and creative collaboration.

Jump right in, learn as I go?

Read the manual first?

Somewhere in between?

I've tended to be the jump right in sort. In fact, I used to joke that when you tell me to jump, I'm in the air before I ask "how high?" I've learned, after numerous wasted efforts, that sometimes it's wiser to slow down, see how things unfold.

Going slow also allows for an internal processing to take place.

Still, one thing I know is that, regardless of the nature of the project, I always start with one thing: doing what I know.

In my previous career, as Clinical Strategist for a global healthcare informatics software company, I authored many different types of technical documents as I moved from assignment to assignment.

As long as I had some sort of example, I could take that and off I'd go.

As in to the break room. Really!

Walk around the department, maybe take a walk outside.

Because what I already knew needed to swirl around with what I was learning, and come together in my mind. Once that was done, I would sit down and type away.

I used to think I was avoiding that particular project until I realised what was happening. That a natural thought process evolved which resulted in quality documents.

I've found the same to be true in writing daily blogs for the last four weeks.

Four weeks ago, when I accepted this 30-day challenge, I tended to write earlier in the day. That has shifted to after dinnertime, which allows me to notice the events and thoughts that come and go throughout the day.

By the time I sit down in the evening to write, it's pretty much already done. In my head. I type the words out, play with them, edit, edit, edit.

While the thought of vomiting does not appeal, I do love how that gives me permission to not worry about how good it is straight off…

Though I do believe that much of what bubbles up is spot on. Cheeky me!

Seriously, the truth lies in telling my truths.

I do what I know.

…freeing the words that have been trapped inside us for decades, and having that conversation

…writing the novel that has the page-turning quality of a Dan Brown

…attaining guru status like Paulo Coelho

…proving our worth to our father

…standing on stage at The Apollo Theatre

…becoming financially secure

…the world recognising the master songwriter we know we’ve always been

…writing the dedication

…choosing the text and art work for the cover

And, of course, that’s all part of it.

It’s the yearning to express that we carry round with us, like a wild animal howling through the dark wood.

Our heart aches- for what?

To find the words that can express the strength of our inner experience (imagined or remembered, owned or given to a fictional character) in words.

To feel. To find the channel for the upsurge of emotion.

To express it

To contain it

Perfectly.

To be heard.

Doing the washing-up, sending a work email, bathing the kids, we sometimes find ourselves inspired by an idea, stopped in our tracks by an image, catching a glimpse of our wild words. The words that want to be expressed, the story that needs to be told.

Like those moments in the forest, on the trail of the wild animal, when we see an amber eye glinting in dusk light, a flash of a tail through the dew-filled undergrowth, a paw print in virgin snow... Tantalising… Calling us to come closer. Warning us to stay away.

There are as many different forms of words as there are creatures in the forest, squeaking, roaring, galloping, crawling, grunting wild creatures all, but whatever the form, the process is much the same.

It has two parts: which must be kept distinct if we are to avoid our human-storyteller-animal freezing (commonly know as creative or writer’s block).

This necessitates trusting that we are all natural storytellers, and knowing that we’re doing something worthwhile (Don’t believe me? Read this.)

Write the draft straight through, from beginning to end, when you’re feeling fresh, and connected to the emotion of the narrator or lead character. (Struggling to connect to the emotions? Here’s a blog that will help.)

Bring in techniques that will help you to express on the lips or the page, what you want to express. Use them consciously, precisely. (Stick with Wild Words for 2017, and you’ll have all the precise techniques you’ll ever need by the end of the year).

After repeated use, the techniques of stage 2 will drop down into the unconscious, and become instinctual. You will find you increasingly use them in the first draft stage.

The process is much the same. Stage 1 is saying what you need to say, without judging yourself. Stage 2 is consciously learning skills that enable you to do stage 1 more skillfully, appropriately and impactfully, the next time around.

We yearn to express ourselves. However, what keeps our words caged is that we also fear it. We are terrified that if all that energy inside is let loose, it will rampage, destroying ourselves, or another. Think of the tiger in the jungle. He’s such a majestic creature. We crave a sighting, but we are panic-stricken at the idea of looking him in the eye.

At Wild Words we don’t just unbolt the door of the cage. That’s not the way to the best self-expression.

If we do that, more often than not, the words cower in the back of their cage, terrified by their change in circumstances. Then we’re faced with our stuttering self on stage, or days spent staring at the blank page. Or, we spit words that we regret, often at those we love most. There’s that tiger attacking the person who unlocked their cage.

And in people with a history of trauma, sudden release of energy can result in patterns of trauma being re-enforced. There’s that tiger attacking your very soul.

No, there’s an art to bringing the aliveness that lies within, out and into form. Rather than crank up the resistance, we work with respect for the survival strategies (those metaphorical bars) that have kept those words in, often for years, out of concern for our safety.

There are techniques, mind-blowing ones (start here) for tempting those wild words out, for opening up that pure channel of communication between our self, our character or narrator, and the reader or listener.

Then we find that our words are living, breathing, perspiring creatures, more vivid, engaging and vital than we could ever have imagined possible.

They rise up through our body, dance off our lips, pour onto the page.

They live fully, broadly, and deeply. And so do we.

Then we have, indeed, cleared a path through the woods to becoming the next J. K Rowling, Kate Tempest, or whoever it is who lights our fire.

And you know what we find once we’ve tracked down our wild words?

Our lives are like clay, malleable and full of potential.

The force of the imagination in the human being is not to be underestimated. As Jonathan Gottschall remarks in his book ‘The Storytelling Animal’, human beings have no trouble at all making things up, i.e. telling stories. In fact, we have trouble not making a narrative out of anything and everything we come across!

Let’s look at the example of deciding to write an autobiography. Ever noticed that in the re-telling of a past event, those who were present can have completely different memories of what happened? In the very act of making memories we select and edit the material of our lives. And when we write down our life story, we necessarily re-edit our already creative memories, to make the narrative work.

It’s not only in re-viewing and recording the years of our life gone by, that we make creative choices. We do it in every new life situation we encounter. We always have a choice as to how we think and act (even if the range of choices available is not necessarily what we would wish). We can realise this, take responsibility for our choices, and thereby feel in control of our life, or, we can see ourselves as a victim of life events over which we have no control. The former gives us strength and health. The latter brings fear and ill health.

Our ability to make choices in our life as a whole feeds in to how well we make choices during the storytelling and writing process. It also gives rise to the evidence observable on the page, and the clues held in the tone, vocabulary, grammar and rhythm of our spoken words. When we make pro-active choices at appropriate times in the storytelling process, we come closer to behaving like the truly wild animal, responding appropriately to its environment. We become better speakers and writers. Writers-in-the-wild.

It’s time to stop thinking of them as flat and unmoving on the page, or as lacking grace, flow and passion when they leave our mouths. It’s time to start regarding them as wild animals in the woods, clay in our hands. They are a physical substance that can be bent shaped moulded, and toyed with until a powerful form arises, seemingly of its own volition.

While it obviously plays a key role, the thinking mind is also partly responsible for creating and sustaining many blocks to creativity. When we involve our bodies as well as our minds when we tell stories, we change the status quo and dissolve many of those blocks. We discover a way of operating that is similar to the way in which animals function in the wild. In this sense, we re-find a ‘natural’ state of storytelling. We become ‘wild writers’ – unblocked, prolific, satisfied and successful in our chosen field.

Put simply, the process goes like this: The storyteller experiences life from an embodied vantage point. (How can it be otherwise? Our body sensations, emotions, thoughts, perceptions and images all reside and influence each other there). They then assigns that embodied experience to their character or narrator. The reader/listener then feels that experience as they read or listen. It is from the physical body of the storyteller, to the body of the narrator/character, and then to the body of the reader, that meaning is transmitted.

Conversely, if they are only aware of their thoughts, not their bodily sensations or emotions for example, the receiver will be impacted very little. The role of the storyteller’s embodied experience is fundamental to the creative process.

Another idea that is key to the Wild Words work is that what happens on the page is a reflection of the behavioural patterns that the storyteller demonstrates in other areas of their lives. When we look at the page or listen to an oral tale, we glean clues to the functioning of the writer/storyteller. Conversely, if you work with your relationship to your embodied experience, you can fundamentally affect what happens on your page, or in the telling of stories (‘true’ or imagined), to others.

At Wild Words, the crafts of writing and storytelling are taught from the ‘bottom up’. This means that the most physical level of the storyteller’s being- the body, is considered the most important focus, and the thinking mind, with its meaning and narrative-making, is of secondary importance. Here we’re turning traditional writing tuition on its head. In the writing world, I’m doing the equivalent of telling you that the world is round when you’ve always been told it was flat. Exciting isn’t it!

Certainly, as writers we have a tendency towards over-thinking, over-analysing, and self-criticism. This often takes us further away from being in touch with a ‘natural state’ of writing, and our innate ability to tell great stories. Many, if not most, writing classes exacerbate this problem, by teaching us to ‘think more’ in order to be a better writers.

When we use only our thinking minds, and set up ideas of what is ‘right’ and ‘wrong’ on the page, it’s always a quick fix. We don’t identify and deal with the source of problems, nor learn to make the most of the opportunities that come our way. Our creativity does not improve sustainably. However, nowhere in this course do I suggest that we jettison our thinking mind completely. It’s a valuable asset to the storyteller-writer, if used correctly. What I do suggest is that we re-prioritise and re-order the process.

We can learn to listen and respond to its cues. To do this we must re-train the body-mind relationship, as well as, where necessary, make unconscious material, conscious. Then we too will have the awareness, and dare I say it, wisdom, to achieve our goals.

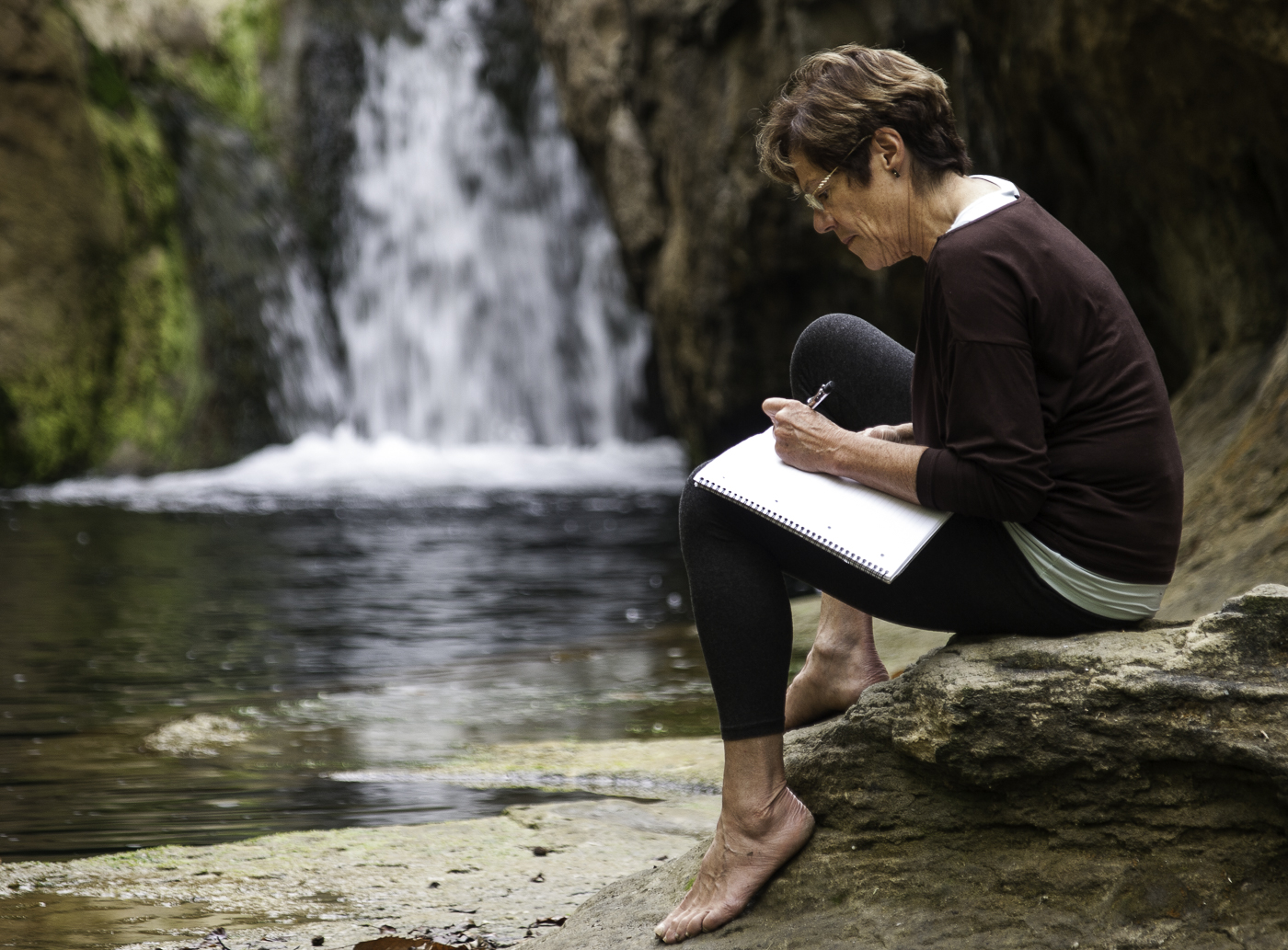

The Wild Words Retreat. Photographed by Peter Reid.

Reading or listening to stories imbued with emotion stimulates much more of the brain than reading an emotionless account would do. The empathy areas light up, and oxytocin, a chemical related to feelings of love and trust, is released.

When our words are imbued with emotion, for both the storyteller, and the listener or reader, it’s like having the wild animal very close, breathing down our neck.

These wild words hook the reader. The power and the passion within them sweeps us along, all the way to the end of the story. There is nothing tame about these words, nothing predictable. They live in extremis. One moment the receiver is roused to laughter and joy, the next they are devastated by tragedy. Hooked by emotion, they journey with the narrator/lead character. It’s quite a trip.

Rachel Shirley gives a relevant example of how to work with emotion on the page. She explains that you could write,

She waited by the door. She felt so frightened, she thought she would begin to panic.

However, it would be stronger to write,

She waited by the door. Her heartbeat thrummed against her ribcage, her mouth tasted like iron and her breaths hitched in her throat.

Although wild words are infused with emotion, as you’ll have noticed in the above example, the emotion is often not named on the page.

Instead the experience of feeling emotion in the body, which is actually the experience of the intensifying of bodily sensations, is described. As these experiences are common to all of us, we know exactly what emotion is being experienced, even if it’s not named. Indeed, it’s more impactful for not being named.

Below is a wonderful (if stomach turning) example of how to work with emotion on the page, from Ian Fleming’s ‘Casino Royal’. Le Chiffre is torturing Bond. Notice how the emotions are never named, but there is attention to the detail of bodily sensations.

Bond's whole body arched in an involuntary spasm. His face contracted in a soundless scream and his lips drew right away from his teeth. At the same time his head flew back with a jerk showing the taut sinews of his neck. For an instant, muscles stood out in knots all over his body and his toes and fingers clenched until they were quite white. Then his body sagged and perspiration started to bead all over his body. He uttered a deep groan.

I applaud that project, and any writer who steps out over the parapet to take part in it. When you commit to the daily word count, it won’t only be others who await the results you’ve promised. You’ll also be setting up high expectations for yourself. The pressure will be on.

For some writers, at some times in their lives, it’s just what they need. NaMoWriMo is a virtual community, where the peer network can guide and inspire superbly.

This is a dangerous pattern for a writer because once we’ve failed to achieve a goal, it is evenmore difficult to achieve it next time. We can end up spiraling down into a vortex of unfinished projects and decreasing confidence.

What we need to do this NaNoWriMo is set ourselves up to succeed not fail. We want to create a virtuous circle, not a vicious one. To do this, it’s imperative that we set realistic goals with regards to how many words we can write each day, given our other life commitments. It’s often better to complete a shorter project than half-finish the next War and Peace.

Even if you write only ten words of a poem a day, or manage to spend 15 minutes in your private writing space, if that fulfills your intention, you’ll feel satisfied. As writers we need to stop beating ourselves up about what we don’t achieve, and notice how much we do achieve.

Good luck!

From March '79

Tired of all who come with words, words but no language

I went to the snow-covered island.

The wild does not have words.

The unwritten pages spread themselves out in all directions!

I come across the marks of roe-deer's hooves in the snow.

Language but no words.

Tomas Tranströmer

(Translated from the Swedish by John F. Deane. You can find the original, and hear it here.)

It’s got me thinking. We can use words, but not really be communicating. Sometimes I’ve been asked to read stories and memoirs, and found they are like that. There may be a set of signs on the page, but they have left me unmoved, and with only a vague sense of the characters and world they are describing.

Conversely, language is not always a set of signs that we can use verbally. It can also be something more subtle- a rhythm, a felt sense, an atmosphere. Communication is the key. The important questions are: How do want to affect our reader? And, how can we convey the essence of the world/person/thing that we are describing? This thought process has led me into the work of Jeanette Winterson. She writes, in Art Objects,

‘The artist is a translator; one who has learnt how to pass into her own language the languages gathered from stones, from birds, from dreams, from the body, from the material world, from the invisible world, from sex, from death, from love. A different language is a different reality; what is the language, the world, of stones? What is the language, the world, of birds? Of atoms? Of microbes of colours? Of air?

So we go on learning our craft, trying to make something meaningful of these black marks on the page.

‘Words but no language…language but no words’.

Write a non-fiction or fiction piece, in prose or poetry, using this line as inspiration.

If you’d like to publish it as guest post on the Wild Words Facebook page, I'd be delighted.

This blog was first published on April 5th 2013.

Wild Words - Nature-inspired creative writing for wild writers and storytellers with Bridget Holding.

Wild Words is a call to express the wild in you. For anyone who has a yearning to express themselves. In conversation, spoken word, storytelling, songwriting, writing (poetry and prose, fiction and non-fiction).

Website by a monk

We unpeel those layers that have attached themselves over time, by finding word portals back to a freshness of thought and expression.